2,000 year-old vitrified human brain yields secrets of the ancient world

Hey! It’s the first issue of my newsletter! Thanks for being here! Today we’re going to talk about a guy whose head exploded almost 2,000 years ago — and the brotherhood known as the Augustales that he was part of.

A lot of odd things were preserved virtually intact when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, burying the cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii under a thick layer of ash. There were election signs on walls, beautiful mosaics, multi-seater toilets, wooden display shelves, luxurious goblets, and decorative wind chimes shaped like penises. Yes, really. And now, a group of scholars have documented their discovery of human brain cells at Herculaneum. They had been vitrified — that is, turned to glass — by the 984° F gas that accompanied the volcanic eruption.

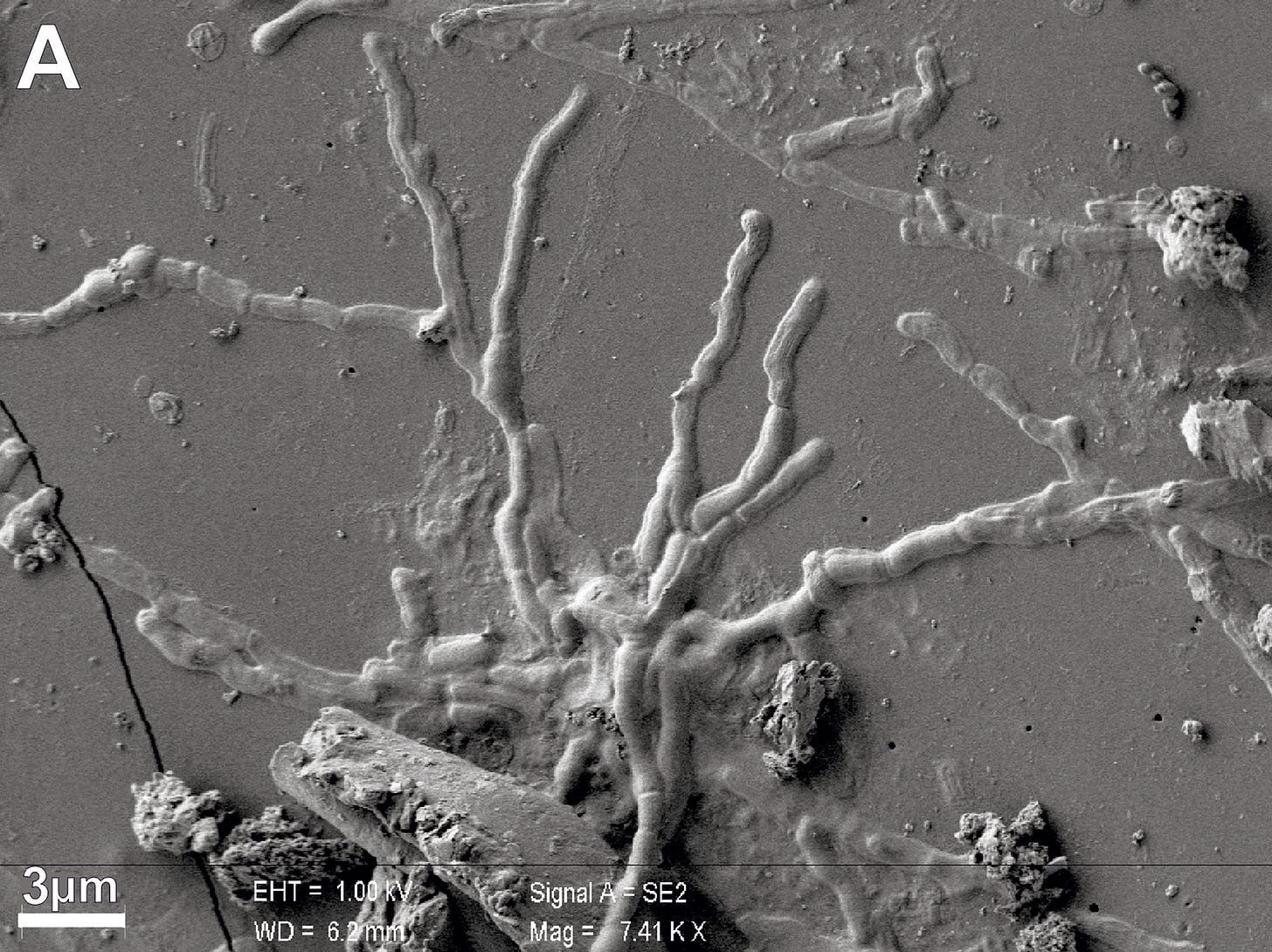

Above, you can see the scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of some neurons from our anonymous glassy-brained friend.

Those neurons once belonged to a man who suffered a terrifying fate: his skull would have exploded in the heat, the fat in his body burned and his soft tissues vaporized. But a few bits of brain survived in his skull, and they turned to glass as they cooled. Using an SEM, scientists identified neurons from the brain and spinal cord by detecting their unique shapes. More intriguingly, the SEM analysis also revealed several proteins manufactured by these kinds of neurons. Two of those proteins are associated with developmental disabilities.

Archaeologists found the man lying on a wooden bed, face down, in a building known as the Collegium Augustalium. I visited the Collegium Augustalium a couple of years ago, when I was researching my forthcoming book Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age. High-ceilinged and airy, with richly painted walls, it faces a busy street corner at the edge of Herculaneum. I wanted to see it because I was fascinated by its history as a meeting house for a civic organization called the Augustales. Founded by the Emperor Augustus, the Augustales were devoted to the betterment of freed slaves, or liberti.

Augustus had expanded the rights of liberti a few decades before Vesuvius erupted, and these meeting halls were a big part of his reforms. Though freedmen were barred from holding public office, they could become wealthy businessmen with a great deal of power. Joining the Augustales allowed them to become civic leaders by rising through the ranks of an organization especially for ex-slaves. It gave them access to politicians, too. When liberti wanted to wheel and deal, they’d invite the aristocratic patrician boys over for a shindig at the Collegium Augustalium.

We’ll never know if the man whose neurons got vitrified was a liberti himself, or if he was the slave of former slaves, tasked with keeping the sumptuous Collegium clean. But no matter who he was, he left his mark — or at least his neurons — for us to decipher.

Read the full scientific article about this discovery in PLoS One.

Where does this story take us?

When I first read about the great glass neurons in Jennifer Ouellette’s excellent article on Ars Technica, I thought: Oh no. Somebody is going to write a bad movie about reconstructing an ancient Roman from their vitrified brain. They’ll pitch it as Jurassic Park crossed with uploads or something. There’d be a lot of hand-waving about the science, and then most of the story would center on how this Roman guy didn’t fit into our world — or, worst case, how modern people had something valuable to learn from him about how it was maybe actually OK that the Romans had slaves because eventually they could get free and join the cool Augustales. No thanks.

I have always believed that the best way to spin up a good speculative response to a weird real-life story is to, well, stick to reality. We are never going to recreate somebody’s brain from a few bits of neurons. But as the researchers pointed out in their discussion of proteins, we still might be able to learn a lot about them. Once we understand how proteins work better, we might be able to figure out whether this guy had a cognitive disability — or whether he suffered from depression or an addiction. We might be able to find out if he was really stressed out, had Alzheimer’s, or had lead poisoning from Roman plumbing. There are a ton of other things proteins might eventually tell us about brain functioning.

Leaving aside the science, we can also reconstruct a lot of his life by understanding what the Collegium Augustalium meant to the men who frequented it. Often when we look back at ancient history, we don’t appreciate the nuances — Romans are either Caesar or a gladiator, and that’s about it. But as Henrik Mouritsen explains in The Freedmen in the Roman World, liberti and their families likely represented three quarters of free people in Roman cities. Think about that: three-quarters of the free people you met on the street in Herculaneum had once been slaves, or were direct descendants of slaves. The fact that our glasshead’s body was in the Augustales’ clubhouse suggests he was part of ex-slave social circles. What if we could couple that information with, say, an SEM image that revealed protein markers for stress and depression? Maybe we’d gain insight into how one ordinary Roman felt about his station in life.

A Roman isn’t just shards of neuron in a petri dish. He is a cultural being, whose identity can be reverse engineered from the place where he slept, and from the laws that restricted his prospects. And his story isn’t some bizarre remnant of a lost past, either. Many of us live in nations and cities that are still shaped by a history of slavery. The world of the Augustales is closer than you think.

Here’s some other stuff I’ve been working on:

I have a new short story out in the anthology Entanglements, edited by Sheila Williams and published by MIT Press. The anthology is about the future of relationships, and my story is called “The Monogamy Hormone.” You can see a reading I did with Sheila and fellow contributor Cadwell Turnbull, whose forthcoming novel No Gods, No Monsters is going to knock your socks off.

In my latest op-ed for the New York Times, I write about a new report by researchers who’ve analyzed a lot of data about the pandemic — and discovered that shaming tactics don’t work. In fact, shame makes people less likely to wear masks and remain socially distant. If you want our cultures to come through this pandemic with a shred of democracy left, check out my article.

October saw the paperback release of my novel The Future of Another Timeline. If you want to hear about my research into time travel and various historical periods in the book, you can watch this video of my talk from late last year at the Long Now Interval series, hosted by the brilliant and much-missed Mikl Em.